Locals on the Front Lines

Nearly two months into a lockdown ordered by Pennsylvania governor Tom Wolf to help slow the spread of coronavirus, many of us are experiencing profound fatigue. Housebound parents of younger children pinball crazily between conference calls and childcare, while some elderly people and those living alone endure long bouts of boredom and loneliness.

But for some, staying safe at home is not an option. Instead, they go each day into the thick of the fight to care for those gravely ill from the virus, often putting themselves and their own families at risk. Frontline healthcare workers — doctors, nurses, medical assistants, paramedics, respiratory therapists, housekeeping staff — are meeting the ferocity of the pandemic with courage and professionalism.

They are also our friends and neighbors. As we’re eating dinner with our families, anesthesiologists intubate critically ill COVID-19 patients in an ICU while their chair sits empty at their own kitchen table. While we sleep, exhausted ER nurses return after midnight to the house down the street, face red with abrasions from hours of being strapped in an airtight mask.

The medical professionals interviewed for this article, all of whom live in our community, say they are not heroes, just people doing their jobs. But many admit they are anxious — worried for their own safety and especially fearful of infecting their families.

A few people contacted for this story did not want to go on record about their experiences in a climate where some health systems have placed gag orders on staff for speaking out, particularly about lack of equipment. But most of these healthcare workers say they feel adequately protected, even as they grapple with constantly changing protocols.

The Big Unknown

Jason Soch drives to his shifts at Riddle Hospital wondering what will greet him. Photo: Jason Soch

Jason Soch, an anesthesiologist at Riddle Hospital who often intubates COVID-19 patients, said he drives to every shift wondering what will greet him. “You drive into the parking lot and you’re walking to the front door and you sort of brace yourself for bad things happening. And then, most days, it’s not too bad. This is the big unknown more than anything, you don’t know how many people are going to come in or how crazy it’s going to be,” he said.

As area hospitals focus on staffing levels to treat a potential surge of patients, many doctors find they are actually less busy, as patients with non-urgent cases stay home. “I think one of the unexpected consequences of the whole COVID lockdown is we’re having much lower patient volumes than we usually do,” said Tom Ball, assistant medical director of emergency medicine at Crozer-Chester Medical Center. “But I wouldn’t say it’s less stressful, because everybody’s a little bit on razor’s edge.” Most people he sees are COVID-19 patients.

John Crawford is a primary care physician with offices in the Mayfair and Kensington neighborhoods of Philadelphia. He said that when the pandemic hit, he and his partner had no guidance about how to care for their at-risk population of inner-city patients. “I said if they have a cough and a fever, I’ll see them — that was the opposite of what we should have been doing,” Crawford said. Now, if a patient has coronavirus symptoms, he sends them straight to a drive-in testing center. He has switched to seeing 95 percent of his patients via telemedicine.

Melissa and Eli Zeserson are both emergency physicians faced with the added task of caring for and helping school their three children, ages 12, 10 and 7. Although reduced patient numbers have made it easier for the Zesersons to alternate their schedules, they’ve had to rely on their eldest son to do more babysitting than usual. Many days, one of them is at work while the other is sleeping after an overnight shift.

“It’s definitely more scary than it usually is to go to work,” Melissa said. She said she catches up on weekly two-hour continuing medical education updates about the virus during her drives to occasional evening shifts at Phoenixville Hospital. “It’s like anything,” she said. “If you feel prepared to enter a scary situation, it makes it easier.”

Constant Risk

Still, there is always a lingering concern about exposure. With more than 1 million confirmed coronavirus cases in the country, there are no comprehensive statistics on the number of infected healthcare workers. On April 12, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated 9,200 healthcare workers had been infected, though health officials say the number is likely much higher, possibly accounting for 11 percent of infections nationally.

For Ellis Choi, an emergency room nurse who teaches graduate nursing classes online, the risk to healthcare workers is indefensible. After seeing some of the area’s first presumed coronavirus patients in early March, Choi — unprepared and untrained on testing — was anxious and angry. “I came home and my anxiety level was through the roof,” she said. “I quarantined myself in my room for 14 days. And I thought, ‘I’m not doing that again. I do not believe that we need to be martyrs. Nobody needs accolades. We just need our equipment.’”

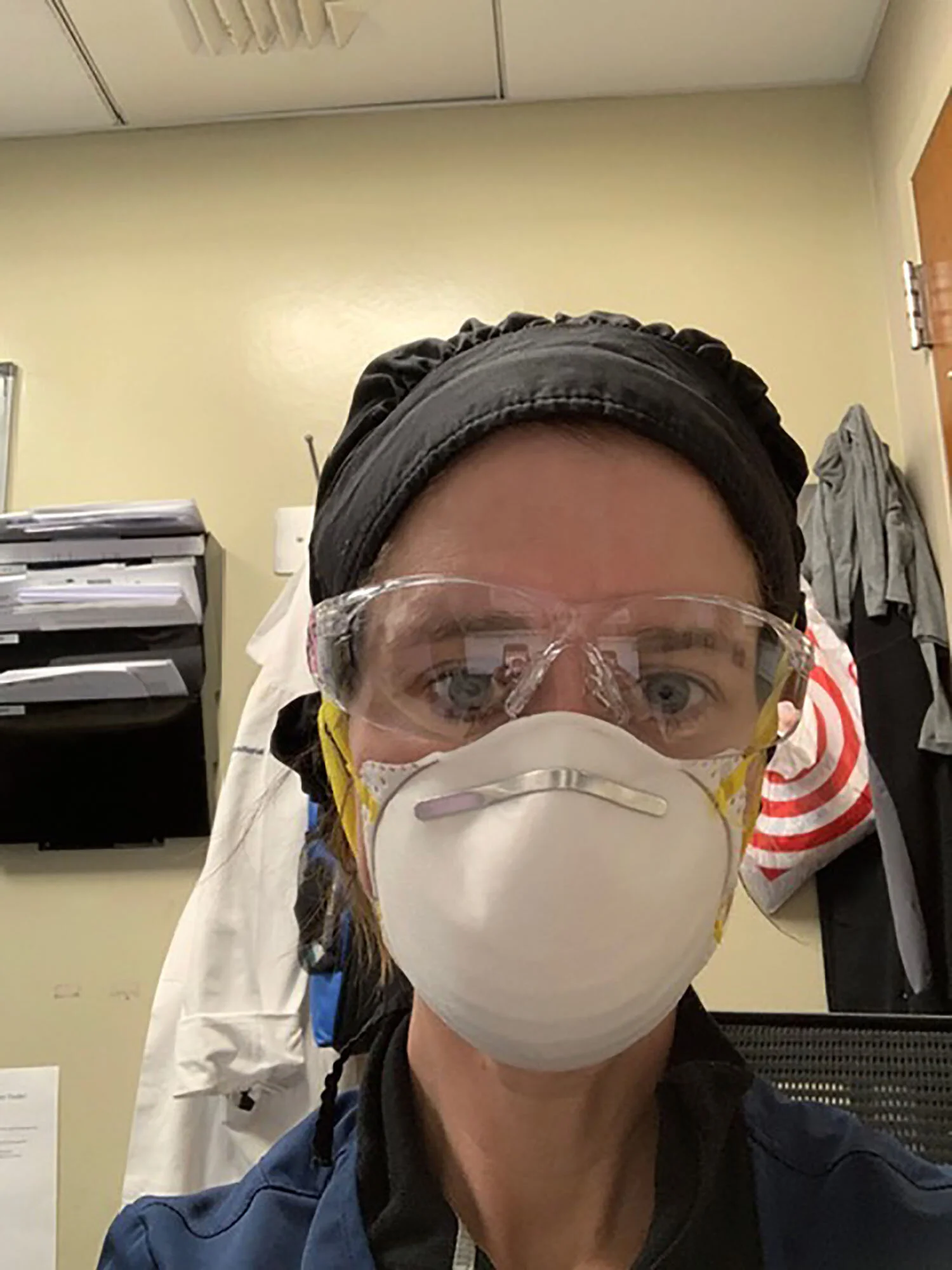

Melissa Zeserson is an emergency physician who lives in Swarthmore.

Melissa Zeserson said she and Eli are very conscious of the fact that they could both get sick. “There are couples that are both intubated in the ICU,” Melissa said. “We redid our wills.” She said they felt compelled to name additional guardians for their children because their original choice was Melissa’s sister — a physician’s assistant who now also treats coronavirus patients.

Soch said he “lives with a little twinge of anxiety all the time.” He said he considered moving out of the house to protect his wife and two children but in the end decided it wasn’t sustainable. “I pretty much just live in my N95 mask at the hospital, and it’s so uncomfortable. But I just do it because the worry of not wearing it is worse.”

All of the healthcare workers interviewed for this story detailed a similar routine when they return home from a shift -- shoes off outside the door, masks stored, clothes stripped off and thrown into a hot wash and then a sprint upstairs to the shower.

Melissa Zeserson recalled the night she returned home from a shift at midnight and undressed in the garage, only to realize she was locked out of the house. Forced to stand outside her front door in her underwear, she desperately rang the doorbell trying to wake up Eli. “And then of course he had to get his own laugh out of it and wouldn’t open the door until I told him the password,” she said.

Humbling Moments

Above all, the most difficult part of their jobs, healthcare workers say, is witnessing people die separated from their families. Kate Degnan, a recovery room nurse who returned to the ICU after 17 years to help take care of coronavirus patients, described a death that occurred on her shift as one of the saddest she’d ever seen. “The family couldn’t be with the patient,” she said. “They could only come in and stand outside the ICU room, escorted, with masks on and watch his last moments. It was horrific.”

“It’s really tough,” agreed Melissa Zeserson. “I’ve cried after a shift when I had a patient that died and I had to tell his wife that she wasn’t able to see her husband — and I had a gown and masks on head-to-toe so no one could see the expression on my face.”

Ball said people need to realize that even mild cases of the coronavirus can cause people to be the sickest they’ve ever been. “I’m very fond of saying to people there are certain things to be nervous about and certain things you shouldn’t be nervous about. But honestly, getting this disease is one of the things you should be nervous about,” he said.

Despite the heaviness of his job, Ball said a bright spot has been the luxury of spending more time with his wife and three sons, ages 14, 12 and 8, who are not scheduled with multiple activities as they would be in more normal times. “I’ve become a lot more mindful and focused on being present and enjoying the day and the moment,” he said. “l honestly think I’ll look back on these days as a great, special family period in our lives.”

Degnan said she finds joy in neighbors down the street who have joined the 7 p.m. tribute to healthcare workers by banging pots and cheering. Others have dropped off bottles of wine, cookies, and even face masks. “I feel like I don’t deserve any of it,” she said. “It’s just so humbling.”