Co-op Steps Up Its Game

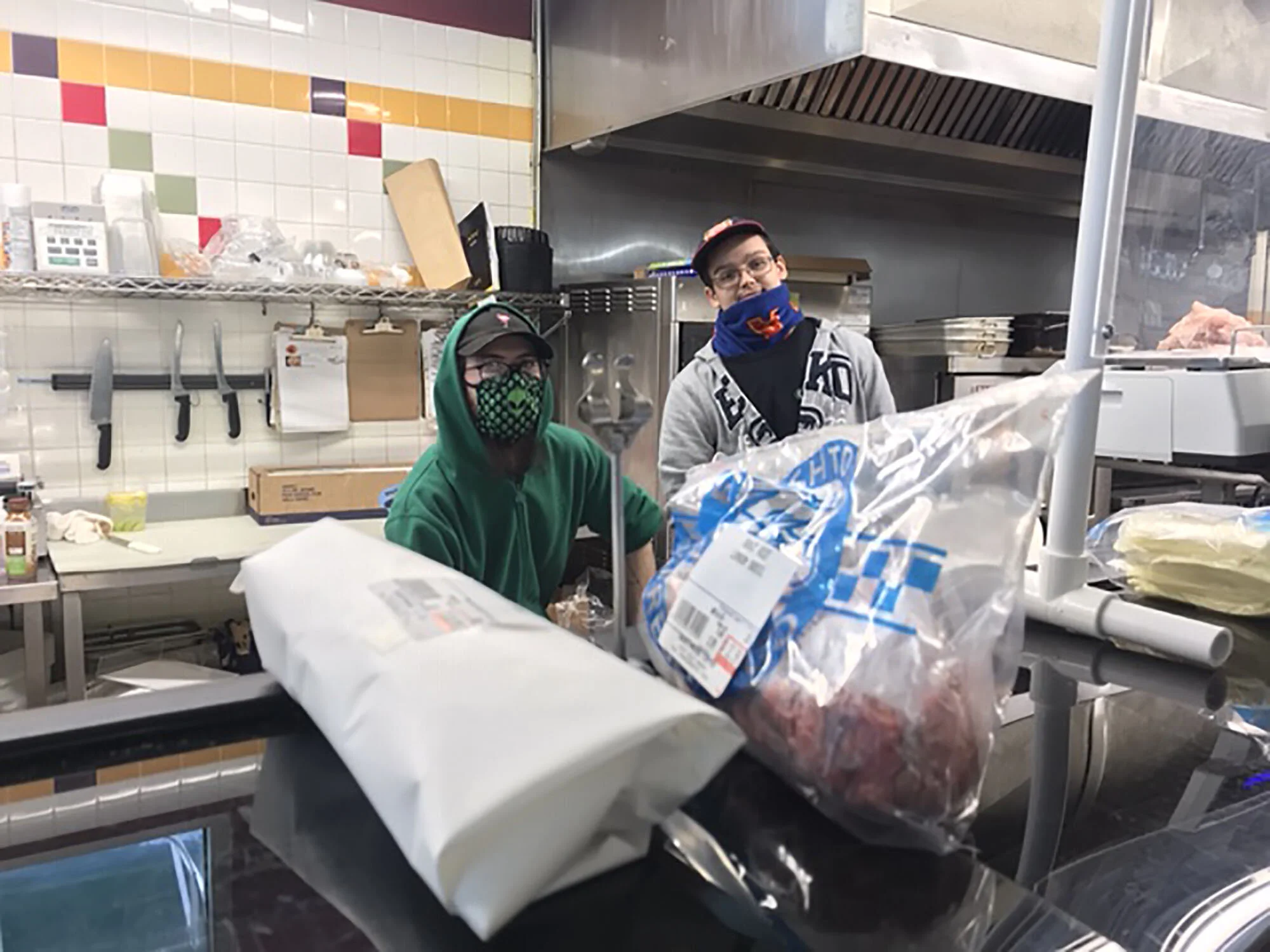

The Co-op staff will receive hazard pay for the duration of the pandemic. Photo: Natalie Bishar

“Thanksgiving on steroids.” That’s how Swarthmore Co-op General Manager Mike Litka refers to the tempo of grocery shopping at the store on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays during the pandemic.

On those three days, the Co-op offers personal shopping for either delivery or curbside pick up. “Before this all started, we had ten deliveries a week,” Litka says. Now, his staff and volunteers can shop for close to 200 customers in a single day. He has waived delivery fees to make it easier for people to stay home.

Co-op General Manager Mike Litka

Since mid-March, Litka has supervised the transformation of grocery shopping at the Co-op. He instituted hand-sanitizing stations outside the store and limits on the number of shoppers inside. He installed Plexiglas barriers between the cashiers and the public. Temporal scanner thermometers, ordered weeks ago, have just come in, and now everyone has their temperature taken before starting work.

“Mike’s been a week or two ahead of the other grocery stores,” says Co-op Board Chair Donna Francher. Early on, he was monitoring the recommendations of the Centers for Disease Control. “His utmost concern is for his staff and for getting people their groceries.”

Unlike many grocery workers, Co-op staff received health insurance and paid time off even before the pandemic. Now they also earn hazard pay, seeing an extra dollar per hour in their paychecks. A virtual tip jar was recently set up for customers who want to show appreciation.

Personal shopping orders ready to go. Photo: Natalie Bishar

In many ways, the Co-op is well positioned to adapt to the new circumstances. “Being a smaller store, we’re able to be nimble and to respond a little bit quicker than some of the big box stores,” Litka says. And the Co-op’s focus on smaller local vendors and producers has meant that he’s able to get regular deliveries. “Our produce and our meats have been 100% in stock.” Only toilet paper and yeast have been hard to keep on the shelves.

Co-op sales are up 25-30% as more people stay home and cook. Average basket sizes have more than doubled. 50 new members have signed up. “Product sell-through right now is sort of like putting butter on a hot roll,” Litka says.

This situation contrasts with recent years.

Some History

The Swarthmore Co-op is a child of the Great Depression.

The institution began as the Swarthmore Fruit and Vegetable Buying Group in 1932. Residents were looking for economical ways to buy fresh produce and support local farmers. What opened in the basement of the Morse family home at 104 Elm Ave. was incorporated into a cooperative in 1937. The Swarthmore Co-op is the third-oldest food cooperative in the country.

As a large sign in the store proclaims, anyone can shop at the Co-op and anyone can join. Member-owners pay a one-time fee of $300, but that doesn’t keep the store going. “Basically our whole revenue comes from people who shop here,” Francher says.

With lots of competition from large stores like Giant and Target and smaller ones like Lidl and Trader Joe’s — not to mention online retailers — the Co-op has struggled in recent years to keep its doors open. Francher says that in 2016, the store lost over $250,000. The next year, her first on the board, Litka was hired. “Mike basically saved the store,” Francher says. Still, the Co-op lost $170,000 that year.

In 2018, the Co-op turned a modest profit.

One of Litka’s changes: rethinking inventory. “He’s a big data guy,” Francher says. He figured out what stock was sitting on shelves, needing to be cleaned and taking up space. For many items — pasta, for example — Litka reduced the number of varieties the store carried. “He would keep a few lower-priced products, and then one or two higher-priced specialty products.”

This freed up room to create an open community space in the front of the store. The Co-op has hosted cooking demonstrations, cookie exchanges, and summer movie nights on a closed-off Lincoln Way outside the stores.

But community events will not be enough to ensure the store’s survival, Francher says. Even with all of the changes, sales continue to decline about 2% each year.

The Board Chair

Donna Francher moved to Swarthmore with her husband Pat in 1990. They’d grown up together in a small town near Syracuse, New York, and been high school sweethearts. When they moved to the Philadelphia area so Pat could take a job with Cigna, Donna started working at DuPont in Wilmington. Swarthmore was halfway in between. “Swarthmore was a little town, and that’s where we grew up,” she says. “In a little town with sidewalks and shops.”

Once she retired in 2017, Francher had time to get to know the community. A volunteer job seemed like a good way to do that. “I like being around food,” she says. “I’ve got a business background.” Team leadership was her specialty. As people cycled off the Co-op board, she started looking for new board members with particular skill sets: PR, finance, food service. “We put together a really nice board that works together well.”

The more the board looked at possible solutions to the store’s financial woes (specialty vendors? An espresso bar?) the more they came to believe there was only one real answer: beer and wine. Grocery sales have a profit margin of up to about 5%. For beer and wine, that margin is closer to 30%. Annually, Francher says, “the profit would be somewhere around $60,000-$70,000.”

In May 2017, Swarthmoreans voted 1,335 to 310 to allow the sale of alcohol in the borough. State liquor laws allow two liquor licenses in a town the size of Swarthmore, and the Co-op hoped to acquire one of them. Then, local property owner Patrick Flanigan unearthed a 19th-century deed restriction prohibiting the sale of alcohol in a wide swath of downtown Swarthmore known as the Biddle Tract. Suddenly, the prospect of selling beer and wine became a lot dimmer.

Since then, the Co-op has spent tens of thousands of dollars and innumerable hours trying to find a legal way forward. They approached the owners of 153 properties in the Biddle tract to collect signatures on waivers saying the property owner did not object to the Co-op selling alcohol.

Three owners ultimately objected to the Co-op’s plan: Flanigan, the Pastuszek family, and Rodney and Deborah Swaney.

On October 2, 2018, the Co-op filed a motion in the Delaware County Court of Common Pleas to set aside the deed restriction. The three objectors opposed the motion. A court date was initially delayed because of a shortage of local judges. Last winter, the Co-op received a date in August 2020. This date now seems likely to be pushed back because of the pandemic.

Taking Care of the Community

The Co-op’s future remains uncertain, but the present is bustling. Litka’s staff of 45 has been bolstered by over 100 volunteers who have answered a call to help with personal shopping, controlling traffic into the store, stocking shelves, and cleaning the store after closing.

Betsy Ffrench has been volunteering for a couple of weeks, mostly filling orders. “We’re all walking up and down the aisles with lists in our hands,” she said. “It’s been fun. It’s a built-in social activity in a time of social distancing.” In addition to feeling as though she is helping people, Ffrench said she’s getting interesting insights into people’s grocery shopping. “I never knew there were so many flavors of potato chips.”

Francher thinks customers feel safe shopping at the Co-op. “You know the people. You know it’s clean.” But she worries that, after the pandemic, people will go back to shopping elsewhere. “Will they continue to support the Co-op?” she wonders.

In the meantime, she’s grateful for the food she can buy there. “I’ve got all the good stuff for a Greek salad with cherry tomatoes and olives and feta cheese,” she says. “So I’m happy.”

To volunteer at the Swarthmore Co-op, sign up here.