People Before Profits: How One Phone Call Launched a Movement to Deprivatize Pennsylvania’s Only Private Prison

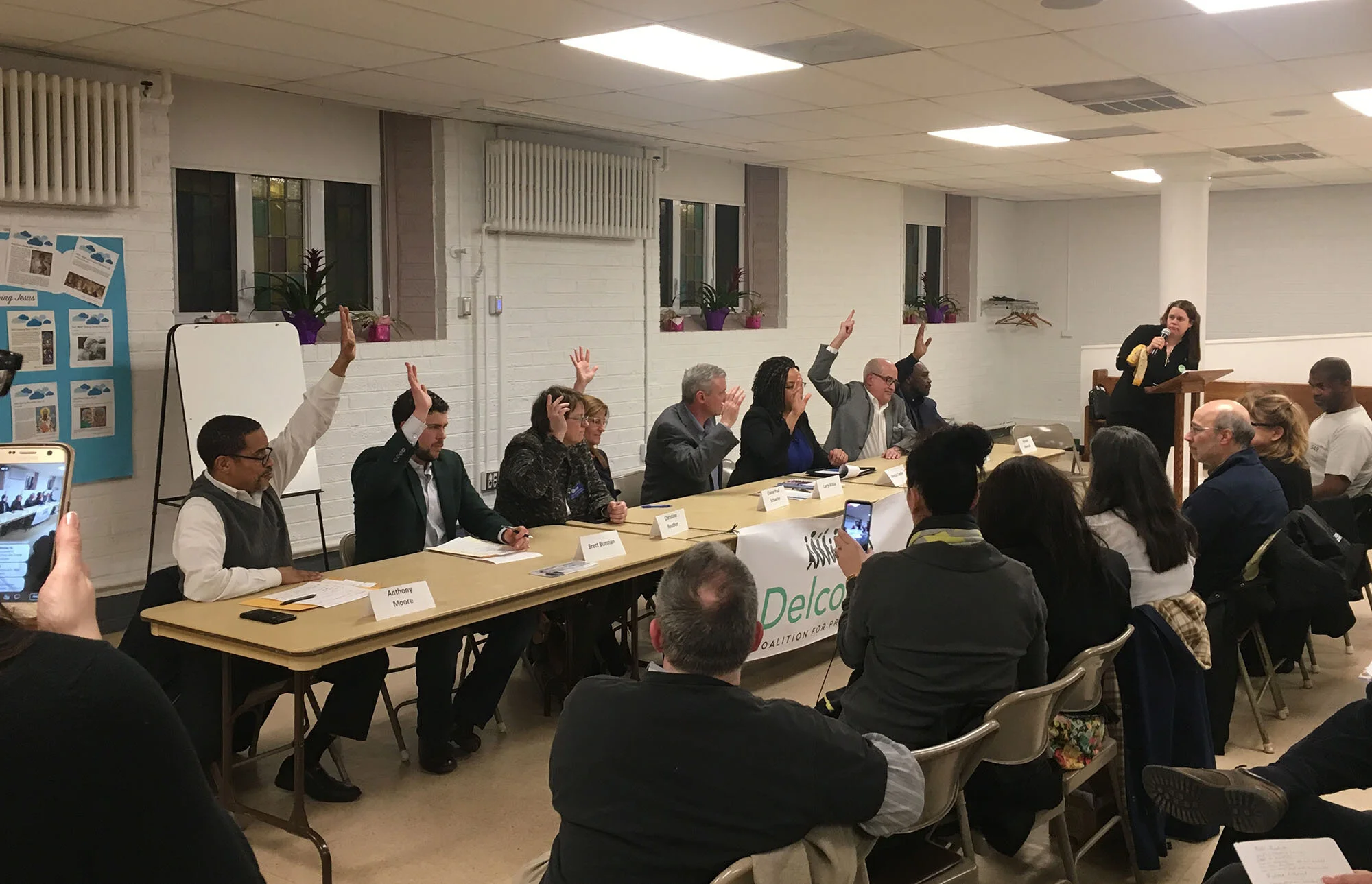

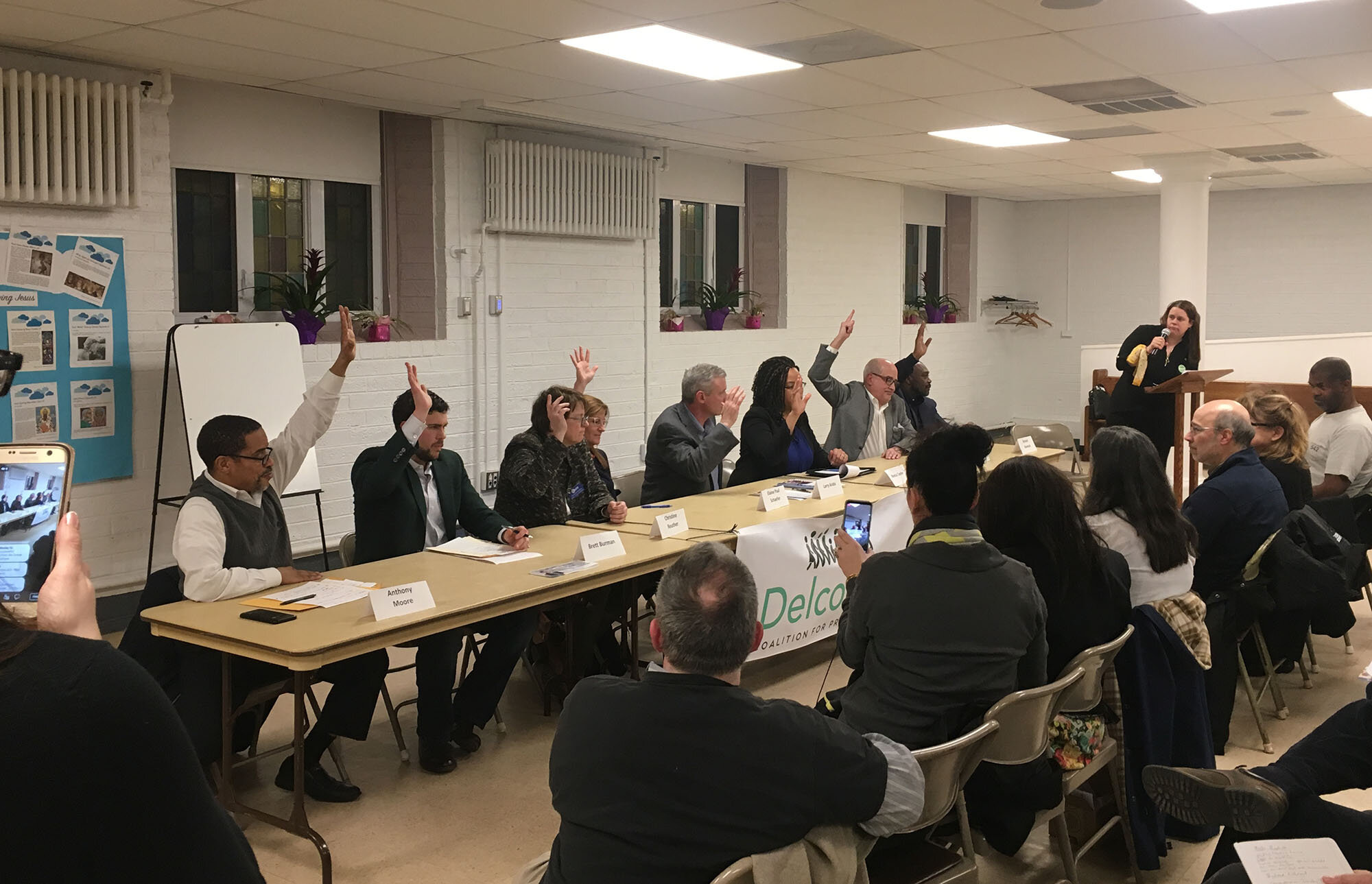

At this candidate forum hosted by Delco CPR in February 2019, current Delaware County Council members Monica Taylor, Christine Reuther, and Elaine Schaefer (then candidates) committed to deprivatizing the George W. Hill Correctional Facility. Photo: Heather Isbell Schumacher

Kabeera Weissman first encountered the George W. Hill Correctional Facility when she was driving her children to a new playground.

Weissman, who would found the Delaware County Coalition for Prison Reform (Delco CPR) in 2017, had recently moved to Swarthmore with her family. As a way of exploring her new county, she began visiting different playgrounds, in different towns, with her kids, then four and one.

One day, she found herself driving up Cheney Road on the way to Thornbury Park in Glen Mills. “You turn right off Baltimore Pike, and then you’re driving down this beautiful residential street,” she recalls. “All of a sudden, there are rows of pine trees and a sign: George W. Hill Correctional Facility. The prison is sort of behind the trees out of sight.” The strangeness of the building — half-hidden, in the middle of a residential neighborhood — made her wonder what was happening inside. But she didn’t think about it for long, just kept driving to the playground.

Weissman was, however, involved in other kinds of social justice work around that time. She helped organize the Swarthmore Solidarity March in December 2016. This event was a response partly to Donald Trump’s election the month before, and partly to the appearance of a swastika on a house down the street. “My grandparents were Holocaust survivors,” Weissman says. “I had no idea what the politics were of my neighbors, so I was asking around...Would people in Swarthmore march?”

The answer was a resounding yes.

The Phone Call

By 2017, Weissman was involved with some local Indivisible groups in Swarthmore and surrounding communities. These are networks of volunteers organizing around progressive causes. One evening, she went to a phone-banking event to express concerns about the jail to Delaware County Council members. The only private prison in Pennsylvania, George W. Hill is managed by GEO Group, which the county pays approximately $50 million a year — about a sixth of the county’s total operating budget — to run. At the time of the phone-banking event, Weissman didn’t know much about private prisons, but she knew she didn’t believe in companies making profits by incarcerating people. So she began calling the council members. “I left some irate messages. And I asked them to return my call. I left my cell number. I didn’t think anything would happen.”

But the next day, then council chair John McBlain called her back.

Their phone call lasted about twenty minutes. Weissman shared her concerns, and she listened to what McBlain had to say. He told her he believed the prison was managed economically and well. But, when she asked him about the people behind bars, “He basically said he didn’t know.”

“I had done this activist training,” Weissman says, “where they teach you to have an ask.” She asked McBlain if he would arrange a tour of the prison for people interested in seeing it for themselves. To her surprise, he agreed.

Weissman started reaching out to people she thought might want to go on such a tour. It turned out that a lot of people did. “It was a coming together of people from different groups,” she says. Jack Stollsteimer — at that time Deputy State Treasurer for Consumer Programs, now Delaware County District Attorney — was on that first tour, as was someone who had previously been incarcerated at the prison.

The Visit

Kabeera Weissman started the Delaware County Coalition for Prison Reform (Delco CPR) in 2017 after a visit to George W. Hill Correctional Facility.

The group tour offered limited chances to talk with prisoners, but plenty of opportunities to ask questions of staff. They visited a female housing unit, a music class, and the law library, among other parts of the prison. They met with prison superintendent John Reilly Jr., who retired last November after allegations of racist and abusive behavior on the job, as well as with medical personnel and guards. At one point, Superintendent Reilly was talking about how things work at the prison when one member of Weissman’s group — a former prisoner — spoke up to refute Reilly’s statement. “It was this powerful moment when you’re sitting in this kind of official meeting and there’s this testimony from someone who knows what they’re talking about,” Weissman says.

That visit was the beginning of Delco CPR. The group began to hold monthly meetings and organize events, including rallies and a bras-and-book drive. Why bras and books? Because prisoners at George W. Hill often have bras with underwire confiscated, and the prison allows incarcerated people few ways to pass the time. “They have some programs,” Weissman says. “But our sense from the people who were there was that they’re very inaccessible, and guards [often] don’t come to get you out of your cell.”

The prison is chronically understaffed, which leads to frequent lockdowns, Weissman explains, “and a whole host of other kinds of abuses and a terrible culture.” Guards, too, suffer in this situation, and Weissman has heard from many prison staff members about bad conditions at the prison.

The Stories

As word about Delco CPR got out, people began flocking to it. Many wanted to tell their stories: about their own incarceration, or their children’s. Parents whose children died in the prison connected with others who shared their experiences. One was Susanne Wallace, whose daughter, Janene, committed suicide at the jail in 2015 after being put in solitary confinement. Wallace, who had mental health problems, had been taunted by a guard when she threatened to kill herself. Shortly thereafter, she hanged herself in her cell. The Wallace family and the prison settled a wrongful death suit for $7 million in 2017.

“It’s heartbreaking,” Weissman says, adding, “It became apparent to me that before this organization was formed, there wasn’t anywhere for people to put their stories.”

With permission, Delco CPR has made those stories public. Members have testified at Delaware County Council and Board of Prison Inspectors meetings. Not that it was easy to get to prison board meetings, which at that time were held inside the prison. One of the group’s early successes was to win video coverage of those events.

A bigger victory came last December, when the prison board was dissolved and a new Delaware County Jail Oversight Board, with members from a variety of backgrounds and representing a range of constituencies, was formed to take its place. Meetings of the Jail Oversight Board are held at the Delaware County Government Center Building in Media.

The members of Delco CPR are likewise diverse. “It’s amazing to see the representation,” Weissman says. “From all over the county.”

The Goals

The group has set its sights on deprivatizing George W. Hill and returning it to government oversight. The Delaware County Council, controlled by Democrats since January, has recently begun work toward this goal. But Delco CPR is also looking toward reforms beyond deprivatization.

A current project, “Writing Behind Bars,” involves collecting cards and envelopes so that incarcerated people can write to their loved ones on the outside. The former prison board would not approve this program, but the new Jail Oversight Board did.

Recently, Weissman has scaled back on leadership work, but stays active behind the scenes. Her children are growing older, and she finds herself talking to them about the work in different ways. “I think that part of raising kids is being honest about the world we live in, and sharing it with your kids, and teaching them to be part of changing it.” She recalls a time, years ago, when she was still living in West Philly and had been organizing a protest. She had been dragging her three-year-old daughter around as she got ready, so the day after the protest, she asked the girl what she wanted to do. Go to the playground? Go to the Please Touch Museum?

“And she says, ‘Go on a protest, Mommy,’” Weissman recalls. “She made a new sign, and she had me take her in her stroller — just herself — carrying her own sign around West Philly.” What did the sign say?

Love Everyone.

Note: this article was written before the current COVID-19 outbreak. Last week, the prison announced that an employee had tested positive for the virus. 11 inmates and 23 employees at the chronically understaffed prison were being quarantined.